Primer

Herein we explain one of the most fascinating results in computer science, Grover’s Search. You will need to be familiar with linear algebra and Big O notation to understand the signficance of this work. If a concept is mentioned but not explained, keep reading, and it will become more clear!

bra-ket notation

Quantum computing is deeply connected to physics. Those familiar with linear algebra will quickly be able to pick up so-called “bra-ket” notation. It works as follows:

Bra-ket notation, also known as Dirac notation, is a standard and powerful way to represent quantum states in the field of quantum mechanics. It was introduced by physicist Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac. This notation facilitates operations between vectors (states) and their duals (operators), which are essential in quantum theory calculations.

In this system, two types of symbols are used:

- Kets or |ψ⟩: These represent a column vector containing complex numbers corresponding to the state’s amplitude for each possible measurement outcome. It is often called an “ket” and denoted using angle brackets (e.g., |ψ⟩). For example, if we have three possible outcomes 1, 2, and 3, the ket may look like:

| ψ⟩ = [a₁, a₂, a₃]ᵀ, |

where each ai is complex amplitude for the corresponding outcome.

- Bras or ⟨ψ| : These represent the conjugate transpose (Hermitian adjoint) of kets and are used to denote dual vectors or bras. A bra looks like:

| ⟨ψ | = [b₁, b₂, b₃*]ᵀ, |

where each bi* is complex conjugate of ai. The star symbol (*) denotes the complex conjugation operation.

In addition to representing quantum states, Dirac notation can be used for expressing inner products between two kets and bras:

⟨ϕ|ψ⟩ = a₁*b₁ + a₂*b₂ + a₃*b₃.

It’s worth noting that the order of multiplication matters in bra-ket notation, as it represents an outer product when taking elements from different vectors (kets).

In summary, bra-ket notation is a fundamental tool for expressing and manipulating quantum states, operators, inner products, and other essential concepts within quantum mechanics.

The Unitary matrix

In mathematics and physics, a unitary matrix is an important concept, particularly in quantum mechanics where it relates to operations on state vectors represented by ket notation. A unitary matrix U satisfies the condition that its conjugate transpose (Hermitian adjoint) multiplied by itself equals the identity matrix:

U†U = I,

where U† is called the conjugate transpose of U and I is the 2x2 identity matrix. There is also the requirement that:

rank(U†) = rank(U).

For a unitary matrix to exist, it must be square (same number of rows and columns), have an even dimension, and its elements are complex numbers. The determinant of any unitary matrix has an absolute value of one, which is a property that ensures the preservation of probability amplitudes in quantum mechanics when state vectors are transformed.

Here’s how you can create a simple unitary matrix in Python using NumPy and verify its properties:

import numpy as np

# Define a 2x2 unitary matrix U

U = np.array([[1/np.sqrt(2), -1j/np.sqrt(2)],

[1j/np.sqrt(2), 1/np.sqrt(2)]])

# Check the property: U†U should equal the identity matrix

identity_matrix = np.eye(2, dtype=complex)

is_unitary = np.allclose(np.dot(U.conj().T, U), identity_matrix)

print("Is U unitary?", is_unitary) # True if U unitary

The example above creates a specific 2x2 unitary matrix and checks whether it meets the criterion for being

unitary by using np.allclose, which verifies that the result of the conjugate transpose multiplication approximates the identity matrix (allowing for some numerical error). This is essential because in practice, floating-point computations may introduce small errors due to rounding and representation issues.

Unitary matrices are fundamental in quantum computing as they represent quantum gates, which are reversible operations on qubits that preserve the total probability of 1. They ensure that a quantum computation can be accurately undone if necessary (as part of error correction), and play a critical role in maintaining coherence across complex computations involving multiple quantum states.

In summary, unitary matrices are deeply tied to concepts like probabilities and preservation of information, making them central not only in theoretical physics but also practical applications such as quantum computing, where they serve as the building blocks for manipulating qubits through gate operations while maintaining the physical laws that govern the quantum realm.

The Adjoint matrix

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage[utf8]{inputenc}

\begin{document}

The \textit{adjoint} or Hermitian conjugate $A^*$ of a complex square matrix $A$ is the transpose of the complex

conjugate of $A$. It can be denoted as:

```math

\[ A^* = (A^\dagger) = \overline{A^T}, \]

where \(\overline{A^T}\) indicates taking the complex conjugate of each element in $A^T$, and then transposing the result. The adjoint is crucial in quantum mechanics because it represents the linear operator corresponding to the adjoint or Hermitian operation on quantum states, which has important implications for measurement and observables.

\end{document}

## The Hermitian matrix

In mathematics and physics, particularly within quantum mechanics, a Hermitian matrix is an important concept

that has unique properties suited to the analysis of observables (quantities that can be measured) and their

corresponding eigenvalues, which represent possible outcomes or measurement results. The term "Hermitian" comes

from Jacques Hadamard and Charles Hermite's names—two mathematicians who extensively studied these types of

matrices.

A matrix A is said to be Hermitian if it satisfies the condition that:

```math

\[ A = A^\dagger \]

where \(\( A^\dagger \)\) (the conjugate transpose, also called the Hermitian adjoint) of a complex matrix A is obtained by taking the transpose of A and then taking the complex conjugate of each element.

The key features that define a Hermitian matrix are as follows:

-

It is square (same number of rows and columns).

-

The elements on the diagonal can be real or complex numbers. However, for off-diagonal elements, each element \(\( A_{ij} \)\) where i ≠ j has its conjugate equal to \(\( A_{ji}^* \)\), where the asterisk denotes complex conjugation. This means that if an entry in the matrix is (a + bi), then the corresponding position across the diagonal will be (a - bi).

-

The important implication of this structure is that Hermitian matrices are inherently stable and self-adjoint operators, which is a central concept in quantum mechanics. Observables have real eigenvalues because measurements yield real values. Moreover, eigenvectors corresponding to distinct eigenvalues for a Hermitian matrix are orthogonal (perpendicular) to each other, which implies that the system has well-defined quantized states.

Hermitian matrices are widely used in quantum mechanics as they correspond to physical observables such as position, momentum, and energy, all of which have real eigenvalues representing measurable quantities in experiments. They also form a special class within the complex matrix algebra known as unitary group U(n), where ‘n’ indicates the size of the matrix.

When solving systems of linear equations or analyzing their stability through methods like diagonalization, Hermitian matrices are preferred due to these real eigenvalues and orthogonal eigenvectors, which simplify many problems in quantum mechanics and engineering fields that involve signal processing or control theory.

the Pauli matrices

The Pauli matrices are four distinct 2x2 complex matrices that form an orthogonal basis in the space of all 2x2 Hermitian matrices, and they play a fundamental role in quantum mechanics, particularly in the study of spin-1/2 systems. Named after Wolfgang Pauli, these matrices satisfy several important properties:

- Orthogonality: The Pauli matrices are orthogonal to each other; that is, their inner product equals zero for different matrices and equals 1 for a matrix with itself when complex conjugated. Mathematically represented as:

⟨σᵤ|σⱼ⟩ = (σᵤ†σⱼ + σⱼ†σᵤ)/2, where |u=1,j=1,...,3>.

- Unitary property: Each Pauli matrix is unitary, meaning its Hermitian conjugate multiplied by itself equals the identity matrix:

σᵤ†σᵤ = I, for all u=1,2,3.

The three non-trivial Pauli matrices are as follows:

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:sigma_one} % Label for cross-referencing in the document

σ₁ =

\left[ \begin{array}{cc}

0 & 1 \\

1 & 0 \\

\end{array} \right]

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:sigma_one} % Label for cross-referencing in the document

σ₂ =

\left[ \begin{array}{cc}

0 & -i \\

i & 0 \\

\end{array} \right]

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:sigma_one} % Label for cross-referencing in the document

σ₃ =

\left[ \begin{array}{cc}

1 & 0 \\

0 & -1 \\

\end{array} \right]

\end{equation}

| These matrices can be represented using bra-ket notation. For instance, if we have a state vector | ψ⟩ representing spin up along the z-axis ( | ↑z⟩), it can be written as: |

| ψ⟩ = √(1/2) | 0⟩ + i√(1/2) | 1⟩. |

| We can apply any Pauli matrix to this ket using bra notation, such as for σ₁ and obtain the new state | φ⟩ resulting from its action on | ψ⟩: |

Hilbert spaces

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage[utf8]{inputenc}

\begin{document}

A \textit{Hilbert space} $H$ is a complete inner product space. In the context of quantum mechanics, it can

represent the state space of a system where physical observables are represented by self-adjoint operators and

states as vectors in this space. A typical element from a Hilbert space could be denoted by an orthonormal basis

$\{e_n\}_{n=1}^{\infty}$, which is indexed by the natural numbers, with each $e_n$ being an eigenvector

corresponding to a quantized observable.

For two elements $u, v \in H$, their inner product can be written as:

\[

\langle u, v \rangle = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} c_n \overline{d_n},

\]

where $\{c_n\}$ and $\{d_n\}$ are the coefficients in the expansion of $u$ and $v$ with respect to the

orthonormal basis. The completeness property can be stated as: every Cauchy sequence $ \{x_k\} \in H$ converges

to an element $x \in H$.

\end{document}

Hadamard Gate

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage[utf8]{inputenc}

\begin{document}

The \textit{Hadamard gate}, often denoted by $H$, is one of the fundamental quantum gates used in quantum

computing. It creates a superposition state from a classical bit, mapping the basis states $|0\rangle$ and

$|1\rangle$ to $\frac{|0\rangle + |1\rangle}{\sqrt{2}}$ and $\frac{|0\rangle - |1\rangle}{\sqrt{2}}$,

respectively.

The matrix representation of the Hadamard Gate is given by:

\[ H = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}

\begin{pmatrix}

1 & 1 \\

1 & -1 \\

\end{pression>

Intuition: the Lost Key-Ring Quandary

Imagine one has found a key-ring on the ground and wants to know which key will open a nearby door. Some thought reveals there can be no better strategy than to try every key one-by-one. In the worst case, one chooses the correct key last by chance.

This metaphor will be instructive to understand the problem of the unsorted database.

“An unsorted database contains N records, and the task is to identify the one record that satisfies a specific property. Classical algorithms, whether deterministic or probabilistic, would require O(N) steps on average to examine a significant portion of the records. However, quantum mechanical systems can perform multiple operations simultaneously due to their wave-like properties.” -Lov K. Grover, 1996

Grover’s Search is a quantum mechanical algorithm that can identify the record in O(√N) steps, and in the same paper proved it is within a constant factor of the fastest possible quantum mechanical algorithm.

Back to the key-ring. In Grover’s search, we will entangle all keys a quantum state, essentially another them to an alternate dimension. We perform a special operation on the quantum state, and after only √N tries, the dimension of the correct key will be the most amplified, while the other dimensions will become exceedingly dimmed. We insert the final key and find that it works!

Grover’s Search

The Oracle

A crucial component of Grover’s algorithm is the use of the “oracle,” which plays a central role in its functioning. The oracle simply tells whether or not a potential state is the actual solution to the query. We can think of this as “finding the key” from the intuition section.

The primary function of the oracle within Grover’s Algorithm is to determine whether a given input state corresponds to a solution i.e. the target or marked item for which we search. It does this by reversibly applying a phase shift and/or an inversion to that specific quantum state depending on its value.

Here’s how it works:

- The oracle is designed such that it has two inputs - the input states (represented as superposition of basis states) we are searching for, and their corresponding output states, which indicates whether they match with our target or not.

- When a quantum state |x⟩ (input state) passes through the oracle, if |x| corresponds to a solution, it applies an inversion operator X; otherwise, it leaves the input unchanged.

-

In terms of matrix representation, when x is equal to the solution, we can write:

θ = -H ⊗ I^n_2 (where H is Hadamard gate and n_2 represents a n-qubit identity)

-

When x does not correspond to the solution, it acts as an Identity operator:

θ = I ⊗ I^n_2

| So effectively, when we pass | x⟩ through the oracle function of Grover’s Algorithm, if | x | is a valid or target state (1), then Oracle will apply an inversion X to this specific input. If not (0), it leaves the quantum state unchanged. This operation marks our solution by flipping its phase from -1 to 1 and vice versayer for non-solution states. |

The use of the oracle enables Grover’s algorithm to amplify the probability amplitude of the desired solutions, making them more likely to be observed when measuring the final quantum state. After several iterations using a combination of Grover’s diffusion operator (which involves applying a Hadamard gate followed by the Oracle function) and this phase inversion property of the oracle, we can obtain an enhanced probability distribution that allows us to find our desired solution with high confidence.

The Procedure

- Apply the Oracle

- Apply the Hadamard transform

-

Perform a conditional phase shift on the computer, with every computational basis state except 0> receiving a phase shift of -1 - Apply the Hadamard transform

| The operating idea here is that the inital random state will be reflected about the orthogonal position to the correct state, | s> until it is most probabilistically aligned with the correct state. A final reading will reveal the correct solution to the oracle. |

Composition of Reflections

For any two reflections with an angle θ, their composition is a rotation of angle 2θ.

Composing two reflections

Reflections in two-dimensional plane

| Now, if we let | A_0> be the vector orthogonal to our solution state, | A_1> the reason for understanding reflection compositions is elucidated: |

Finally, we observe:

Seen in another light, we leverage the arcsin estimation formula for small theta, and of course for N » 2, we do have a small theta indeed.

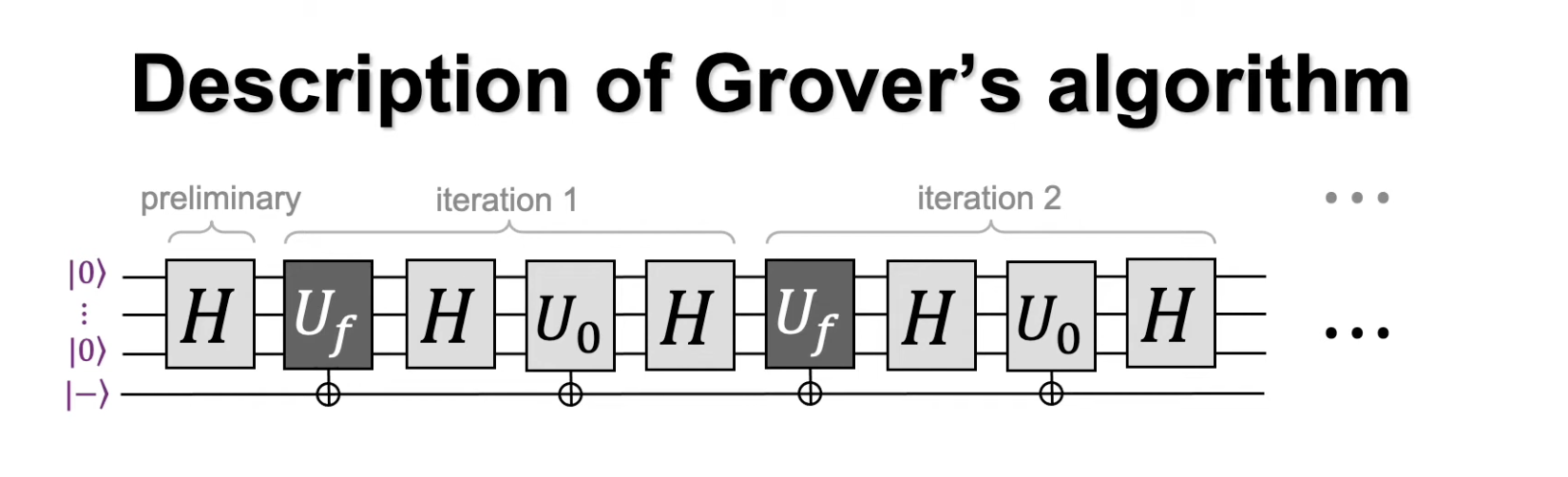

The topic of quantum circuit gates is another topic requiring its own deep dive. We couch that dicussion while providing a diagram for Grover’s Search. The curious reader can delve deeper into this topic for deeper understanding.

Conclusion

Most databases are indeed structured. Therefore, the unsorted nature of the problem appears contrived. Moreover, given the difficulty of maintaining quantum-classical interface and the information loss of qubits, it is unlikely Grover’s Search will be used to solve any pressing computations any time soon.

Nevertheless, the algorithm can be used in other quantum simulations to calculate otherwise intractable calculations.

I hope you enjoyed this introduction to this fascinating result in computer science!

Major Key Alert! 🔑💰

Sources

L. K. Grover. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. Nov. 19, 1996. arXiv: quant- ph/9605043.

M. A. Nielsen and I. L. Chuang. Quantum computation and quantum information. 10th anniversary ed. Cam- bridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 676 pp. ISBN: 978-1-107-00217-3.

TODO: redo the formatting